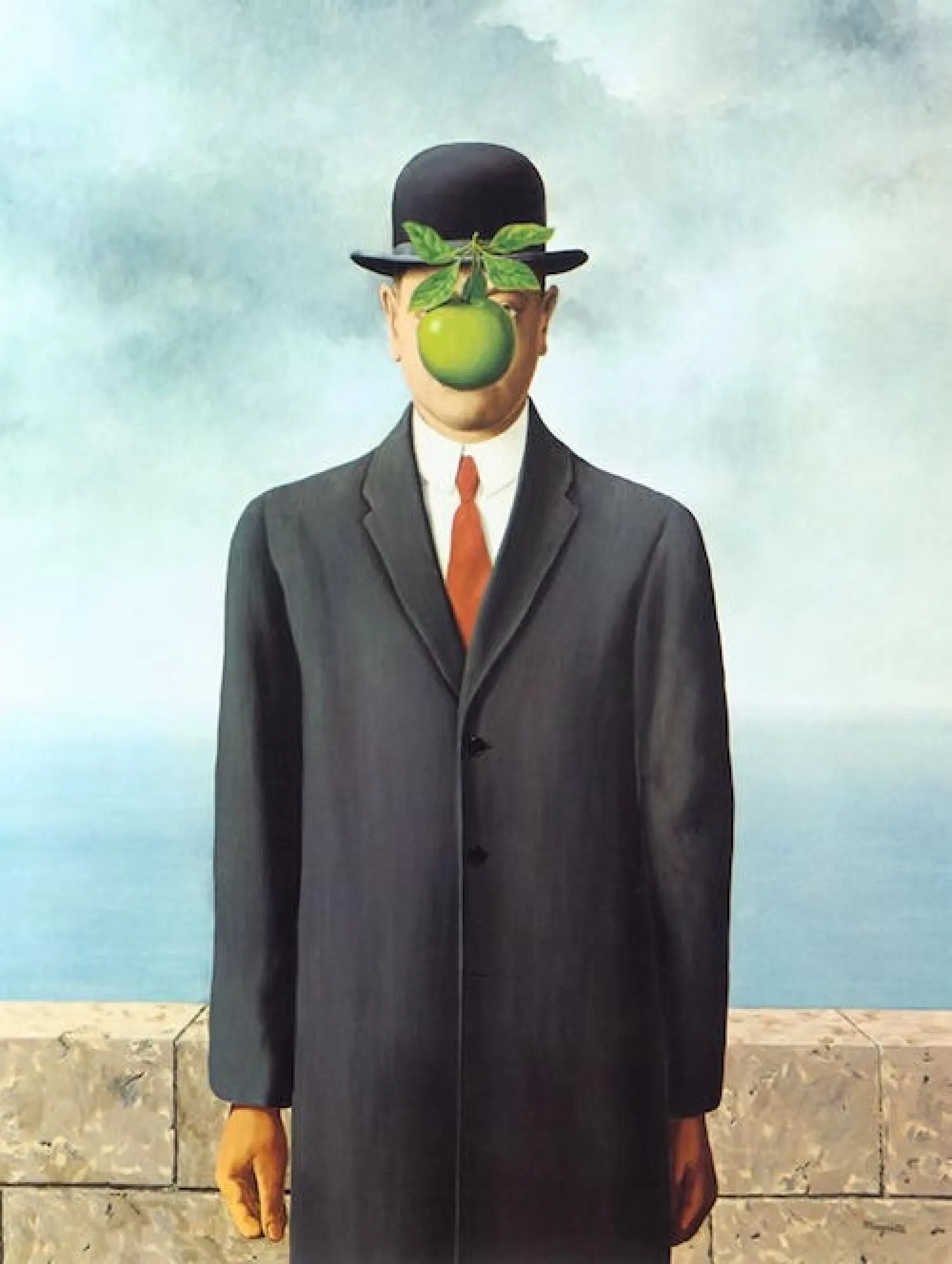

Readymades were everyday objects that could be bought and presented as art with little manipulation by the artist. The pieces were often chosen and assembled by chance or accident to challenge bourgeois notions about the definition of art, creatvity, and their purpose in society.

Chancewas used to embrace the random and the accidental as a way to release creativity from rational control. In addition to loss of rational control, Dada’s lack of concern with preparatory work and the celebration of marred artworks fit well with the Dada rejection for traditional art methods, questioning the role of the artist in the artistic process.

Humor and irony were key to the Dada beliefs that nothing has intrinsic value. Irony also gave the artists flexibility and ability to embrace the craziness of the world around them, thus preventing them from taking their work too seriously or from getting caught up in perfectionism.

Irreverence, tied closely to Dada humor was a crucial component of Dada art, whether it was a lack of respect for bourgeois convention, government authorities, conventional production methods, or the artistic canon.